Legacies of El Yunque Rainforest: Past, Present, and Future

- christineysit

- Jan 19, 2022

- 8 min read

Updated: Jan 23, 2022

***Updated January 23, 2022 to provide a clearer explanation of rainfall across Puerto Rico.***

What stories does El Yunque hold for us? How has it changed over time? Why is the rainforest only in that one part of Puerto Rico? In today's post, I answer these questions while telling the story of El Yunque National Forest.

El Yunque Rainforest and the U.S.

As the only the rainforest of the United States National Forest System, El Yunque National Forest is a unique gem within the U.S. However, it is important to recognize the underlying implications of this fact. Yes, El Yunque is a special and unique place simply by existing. At the same time, El Yunque is a legacy of Puerto Rico's territory-colony existence under the U.S. Puerto Rico is a part of the U.S., but its people hold no power in the U.S. government. Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens, but they cannot vote in U.S. elections (1).

In the same way, El Yunque is distinctly of Puerto Rico, yet its existence serves the U.S. It is managed by the U.S. Forest Service. Its research is often completed by non-local researchers. When we praise the existence of El Yunque within the National Forest System, we celebrate a country that historically has and to this day continues to colonize the archipelago of Puerto Rico. This is why I believe it integral to first acknowledge this aspect of El Yunque's history.

***Disclaimer: I can't possibly cover the entire history Puerto Rico and the political dynamics that exist in a single blog post. I do my best to give context, but please understand this is not an all-encompassing post.***

Borikén to Puerto Rico

Hundreds of years before the island's colonization, the indigenous Taíno people were the first inhabitants of Puerto Rico (2). To the Taíno, the island was Borikén (or Borinquen), the "Land of the Valiant and Noble Lord" (3). Though it is widely believed the Taíno died out when the Spanish arrived, their legacy is survived by the Puerto Rican people, who proudly show their heritage in referring to themselves as Boricua. (You can read more about the Taínos here.)

The beginning of the end for the Taíno was 1493, when Borikén's first colonist arrived, Cristóbal Colón (Christopher Columbus), thus beginning the history of colonization (more detailed history here). In the early 1500's, Borikén was renamed Puerto Rico ("Rich Port") (4). Fast forward almost 400 years, and 1898 marks the year the United States took over the territory from the Spanish. During this exchange, the U.S. also gained 5,018 hectares of forested land (today's El Yunque Forest) in the Luquillo mountains (4).

Historical Land Use Change

The original 5,018 acres of forested land have undergone many names over the years: first the Luquillo Forest Reserve in 1903, later renamed the Luquillo National Forest, then the Caribbean National Forest, finally settling on El Yunque National Forest in 2007 to represent the heritage of the forest (more El Yunque history here).

The 1800s were a time of increasing land cultivation in the Luquillo mountains, where coffee, bananas, sugarcane, and charcoal were produced. This continued until 1899, when San Ciriaco Hurricane, the most deadly hurricane in the history of the Atlantic basin, hit the island (6). San Ciriaco led many to abandon their coffee plantations and farms, beginning the reforestation of the region.

From 1936 to 1988. people migrated out of rural areas towards urban areas, which increased in density by 2000% (5). This led to transitions across the island of high-intensity agricultural lands into dense forest.

El Yunque Forest, which was a region of timber and charcoal production as well as coffee and sugarcane. With the transition of the rest of the island, the forest site shifted from timber and charcoal production to a place of research and recreation.

The Beginning of Long-Term Studies

The 1960s mark the beginning of long-term ecological studies in Puerto Rico with Howard T. Odum's research the effect of radiation in the forest (5). However, most of the "long-term" studies were relatively short. Odum's own was only five years, and subsequent studies lasted between less than a year and up to a decade (5). It isn't until 1990, ten years after the establishment of the U.S. Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) Program, that the Luquillo Forest Dynamics Plot (LFDP) Tree Census begins.

The LFDP Tree Census is the tree census I am working on this year. Occurring every five years, it has lasted thirty-one years. I am working on the seventh census for the only rainforest the U.S. has managed to own.

Rainforest - Why Here?

You may wonder: why a rainforest there?

Most of us know that the two defining features of a rainforest are hot temperatures and a lot of rain. What you may not know is that there's more to it than just heat and rainfall. Near the equator, there are powerful winds that blow from the east to the west, the trade winds. It doesn't matter where you are in the world, as long as you are between 0° and 30° latitude, the winds will usually blow east to west. As with any rule, there are exceptions, but the pattern exists nonetheless. This is explained by the Coriolis Effect.

These powerful winds travel along the ocean, picking up more and more water vapor. Once the winds hit the thousand-meter high Luquillo Mountains (7), the mountains direct the winds high in the sky. At higher and colder altitudes, water more easily changes from gas to liquid form. Liquid water, being heavier than air, then falls. Thus rainfall leading to...rainforest.

Rainfall in Puerto Rico - Who Gets It?

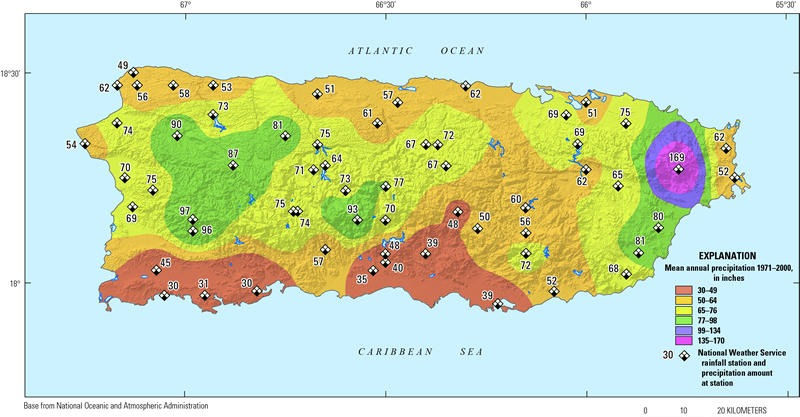

Most of the water falls as rainforest rain on the Luquillo Mountains, leaving little water for the rest of the island. This drier area is commonly called a "rain shadow" and can be seen in the Puerto Rico map below. In the map, the Luquillo Mountains are easily visible as the pink and purple areas of high annual rainfall. As the east-to-west trade winds continue west along the island, they continue releasing rainfall until no more water can be squeezed out at the lower altitudes and warm, surface temperatures. Look directly west of the Luquillo Mountains, where the annual rainfall levels quickly decrease.

More rain can be squeezed out if more mountains along the westward path can redirect the winds once more into the colder, higher altitudes. Luckily, the Cordillera Central (Puerto Rico's mountain range in the center of the island) cater exactly to those needs. They redirect the winds upwards, wringing out the water. However, there is less available water because most of it fell earlier on the Luquillo Mountains.

The Past Reflected in the Present

The rainforest itself shows the legacies of previous land use in which species live there today. You'll see in the chart below that the western central part of the Luquillo Forest Dynamics Plot contains a group of breadfruit, coffee, and mango trees [9]. In addition, you can see a group of more coffee trees at the top right of the diagram as well as historic oxcart trails throughout the plot. Scientists used this data in conjunction with interviews with elderly locals and U.S. forest service historical sources to gain a clearer picture of the past land use of the forest plot [9]. It's a little ironic that the original researchers specifically picked this plot because they thought it was untouched by human influence. Lo and behold, once studies began, the agricultural land use legacies came to light to show more than a bit of human influence! If only they had spoken to the locals and looked at historical records, they would have known.

What the Future Holds for the Rainforest

Many people ask what the future holds in store for us in the face of climate change. El Yunque, due to its tropical location and frequent extreme weather disturbance, can provide some answers. This is because Puerto Rico, like many other tropical places, has already been experiencing the effects of warming tropical temperatures and increasing extreme weather events (tropical storms and hurricanes).

Intense disturbances like hurricanes damage forests, but they also change how forests exist and use their energy. With broken and fallen trees and tree leaves, forest trees spend years recovering from the damage. Taller trees, being more exposed to wind damage, are especially impacted. This means that shorter trees, which are more protected from the wind, have the better survival strategy to survive hurricanes. Hurricanes will damage taller tree canopies, and one result is a lower average canopy height for the forest [9].

Since hurricanes are expected to hit Puerto Rico more intensely in the future [8], it is expected that the forest will become shorter and shorter in order to adapt to the increased disturbance [9]. The graph below shows a more visual representation of this. In 1989, Hurricane Hugo caused a decrease in a average canopy height from around 22 meters to 9 meters. The forest spent a few years recovering, growing to an average of 15 meters, but then BAM! Hurricane Bertha and Hurricane Hortense in 1996 lead to another decrease. Then, repeat another recovery period for a few years until 1998 Hurricane Georges and another drop in canopy height.

A 1991 report by Scatena and Larsen estimated that strong hurricanes would hit the Luquillo Mountains every 50-60 years [10]. After 1998 Hurricane Georges and 2017 Hurricane Maria, this estimate changed. It is now expected that the Luquillo Mountains will experience more frequent hurricanes occurring every 39-44 years [11].

Lessons of the Day?

Hopefully, anyone who has read this far will see that science isn't only about experiments and research done in laboratories. It's also about listening to the stories of the places around us. If done correctly, there will always be more than one story to tell, and these stories can inform us for the future. In the face of climate change, forest ecosystems across the world are adapting, and we need to learn from them.

That's it from me today! See you in the next post!

Links for more information about:

Taíno Indigenous People: Figueroa, I. "Taínos." El Boricua. July 1996. <http://www.elboricua.com/history.html>.

Puerto Rico Colonial History: "Puerto Rico." Yale University, Genocide Studies Program. N.d. <https://gsp.yale.edu/case-studies/colonial-genocides-project/puerto-rico>.

History of El Yunque Rainforest: "History and Culture." USDA Forest Service. N.d. <https://www.fs.usda.gov/main/elyunque/learning/history-culture#:~:text=The%20forest's%20current%20name%2C%20El,covered%20much%20of%20the%20time>.

Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) Program: "About the LTER Network." LTER Network. N.d. <https://lternet.edu/about/>.

Coriolis Effect: Met Office - Learn About Weather. "What is global circulation? | Part Three | The Coriolis effect & winds." [Video]. Youtube. March 2018. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PDEcAxfSYaI>.

TRACE Warming Experiment in a different part of El Yunque: https://www.forestwarming.org/about-us

Rain Shadows: Means, T. "What is a Rain Shadow?" May 2021. <https://www.treehugger.com/what-is-a-rain-shadow-5185265>.

Sources

Peón, H. "It Is 2020, and Puerto Rico Is Still a Colony." Harvard Political Review. November 2020. <https://harvardpolitics.com/puerto-rico-colony/>.

"Taino Indian Culture." Welcome to Puerto Rico! N.d <https://welcome.topuertorico.org/reference/taino.shtml#:~:text=Ta%C3%ADno%20Indians%2C%20a%20subgroup%20of,arrived%20to%20the%20New%20World>.

"History, A Brief History of Puerto Rico." Discover Puerto Rico. N.d. <https://www.discoverpuertorico.com/island/history#!grid~~~random~1>.

"Puerto Rico." Genocide Studies Program, Yale University. N.d. <https://gsp.yale.edu/case-studies/colonial-genocides-project/puerto-rico>.

Harris, N.L. et al. "Luquillo Experimental Forest: Research History and Opportunities." EFR-1. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2012.

"1899- San Ciriaco Hurricane." Hurricanes: Science and Society. N.d. <http://www.hurricanescience.org/history/storms/pre1900s/1899/>.

"Luquillo Mountains, Puerto Rico." Earth Observatory, NASA. December 2007. <https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/8453/luquillo-mountains-puerto-rico>

"Hurricanes and Climate Change." Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. N.d. <https://www.c2es.org/content/hurricanes-and-climate-change/>.

Zimmerman, Jess. "Land-Use Legacies and Hurricanes in Puerto Rico: Nature, Consequences & Future." [PowerPoint Presentation to 2021 Tree Census Interns]. September 2021.

Scatena, F. N., and M. C. Larsen. “Physical Aspects of Hurricane Hugo in Puerto Rico.” Biotropica 23, no. 4: 317–23. <https://doi.org/10.2307/2388247>. 1991.

Brokaw, N.; Ward, S.; and Chevalier, H. "Hurricanes and the Future of El Yunque National Rainforest, Puerto Rico." International Forestry Working Group Newsletter, Working Group B3: page 10. <http://www.orrforest.net/saf/Dec2018.pdf>. December 2018.

Snyder, M. "The Orographic Effect And Its Effect On The Weather." Weather Station Lab. December 2020. <https://www.weatherstationlab.com/the-orographic-effect-and-its-effect-on-the-weather/>.

"Climate of Puerto Rico." Caribbean-Florida Water Science Center (CFWSC). April 2016. <https://www.usgs.gov/centers/caribbean-florida-water-science-center-%28cfwsc%29/science/climate-puerto-rico>.

Comments